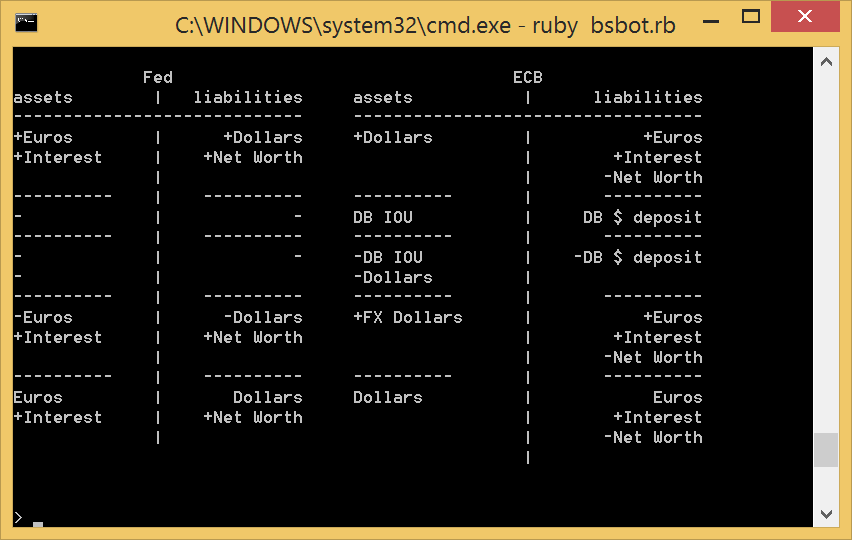

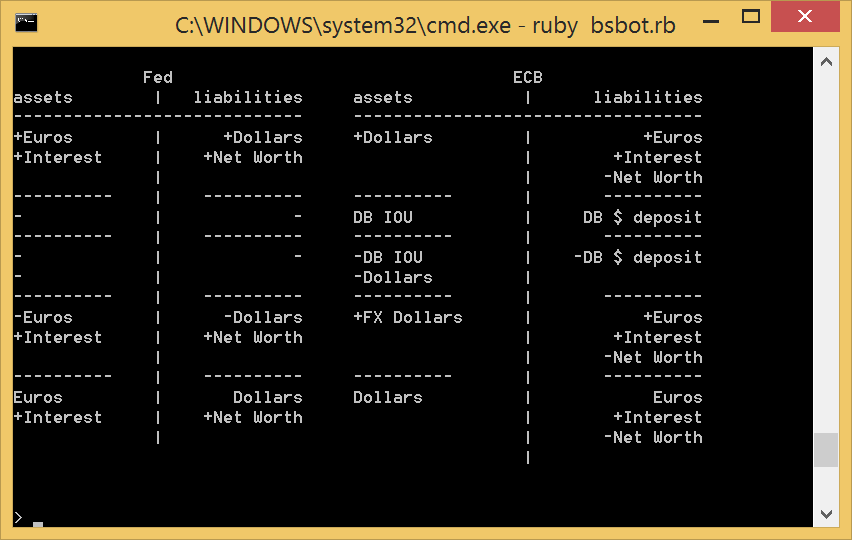

| Notes: Transactions are separated by "----------". |

| "-" by itself as an entry is a placeholder. |

| "+" indicates a balance sheet expansion; |

| "-" followed by words represents a contraction. |

| "DB" stands for Deutsche Bank in my hypothetical, imagined example. |

Script that produced the output in the image above: http://subbot.org/bsagent/dialogs/centralbankswap.script

Raw output of the script when read by bsagent: http://subbot.org/bsagent/dialogs/centralbankswap.output

(Text version of the balance sheets in the image above is at the bottom)

This exercise is based on examples in Perry Mehrling's paper: Elasticity and Discipline in the Global Swap Network

The first transaction shows the initial central bank currency swap: The Fed gives the ECB Dollars and receives Euros, and Interest (Mehrling quotes 100 basis points).

The second transaction depicts the ECB loaning Deutsche Bank dollars. The third transaction shows the ECB writing off the DB loan. The ECB has lost the Dollars it got in the initial swap.

The fourth transaction shows the ECB buying dollars for Euros in the private FX market, paying a certain Interest or Premium. The ECB gives the Fed back the Dollars it got in the initial swap. The Fed contracts its balance sheet by the amount of the initial swap, destroying the created liability dollars and returning the Euro assets to the ECB. Note that the Fed's balance sheet remains somewhat expanded as a result of the Interest agreed upon in the initial swap. To balance the expanded Interest asset, the Fed expands its "Net Worth" liability. (Might the Interest be denominated in Euros?)

The fifth transaction shows another option: the ECB asks the Fed to roll over the swap. Thus both the Fed's and the ECB's balance sheets remain expanded as long as they both agree to continue rolling the initial swap over.

If the price of dollars in Euros went up during the swap period, the ECB can roll the first swap and pay less in interest than it might for more expensive dollars. If the price of dollars in Euros goes down during the swap period, the ECB might get a better interest rate from the market than the Fed's swap rate. In the latter case, the ECB could end the swap by paying the Fed back dollars it buys in the private money markets.

Forward swap rates can lock in the ECB's interest costs at the start, so the ECB can take on exactly the risk it is comfortable with.

At the end, the ECB's balance sheet has lost Net Worth. But profit is not a motivation of central banks. The central bank can create a Euro deposit liability, balancing it with some dummy asset, and replenish Net Worth. Or, simply accept a diminished Net Worth since, for central banks, it does not matter.

The ECB might also perhaps use an exotic, poorly-understood (by me) instrument such as a forward option, which would allow, one imagines, a purchase of dollars for Euros at the lowest rate across the period.

Bottom line: the ECB borrows Fed-created dollars at a rate it cannot do worse than, and may very well do better than through the use of private money markets and financial instruments.

Private banks and corporations also use private sector mechanisms to keep risk's greatest downsides known and acceptable, while providing hedges that may well provide greater-than-expected profit. In crisis times, the central banks step in to provide US dollar liquidity in unlimited amounts, using central bank swaps as one channel.